Jos VAN MERENDONK

The Netherlands

Jos van Merendonk (b. 1956, The Netherlands)

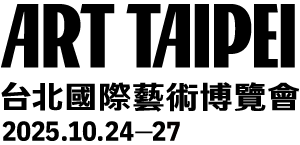

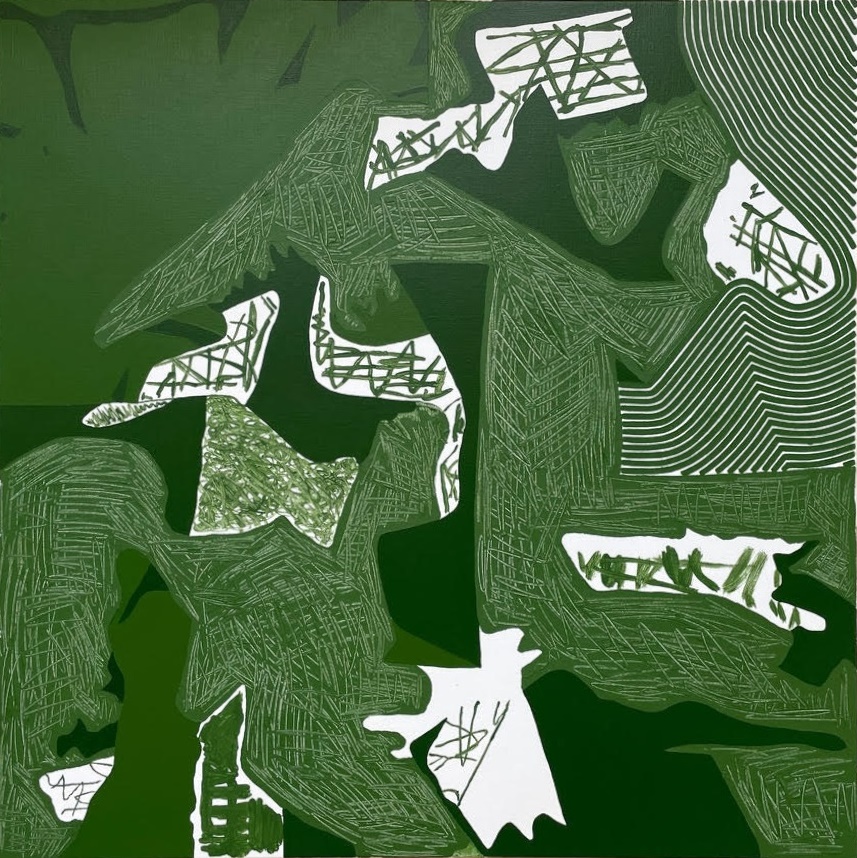

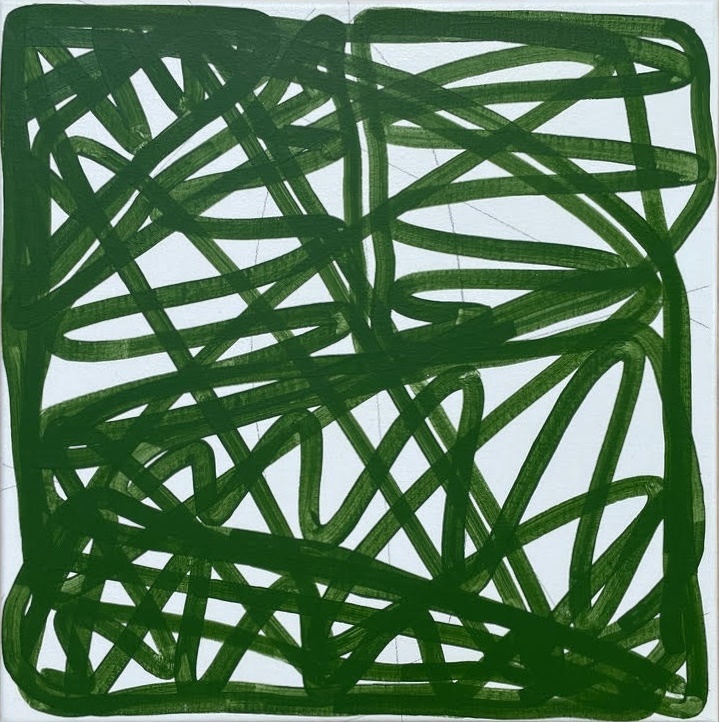

Since the 1980s, Jos van Merendonk has centered his artistic practice around a single, unmistakable element: the green brushstroke. This recurring motif functions as both a formal gesture and a conceptual inquiry into the fundamentals of painting—paint, gesture, and canvas.

Through layers of accumulation and variation, the green brushstroke becomes a metaphor for art history itself: echoing the physicality of Abstract Expressionism while simultaneously challenging notions of repetition and self-generation within painting. What appears to be a limitation unfolds into an infinite field of possibilities.

At Art Taipei 2025, Van Merendonk presents recent works that continue his exploration of painting under self-imposed constraints. Calm yet intense, his paintings embody a rigorous spirit of experimentation and offer a resolute response to the future of abstraction.

The Raving Silence

On Jos van Merendonk

“–See if he is not cutting it into slips, and giving them about him to light their pipes!–'Tis abominable, answered Didius; it should not go unnoticed, said doctor Kysarcius–[pictogram: a hand points to the right] he was of the Kysarcii of the Low Countries.

Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman[1]

“The fields are greener in their description than in their actual greenness.”

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet[2]

Green calls the shots in Jos van Merendonk’s paintings. A powerful, yet introvert green throws the viewer back onto himself; the colour signifies green, but simultaneously questions the sensorial experience of green. After all, memories of the natural green world inhabit us; in our mind there shines as it were an eternally green slide. But this inner ray gets in the way of the art experience, it interferes, intersects, rubs against it, drawing the viewer into consternation.

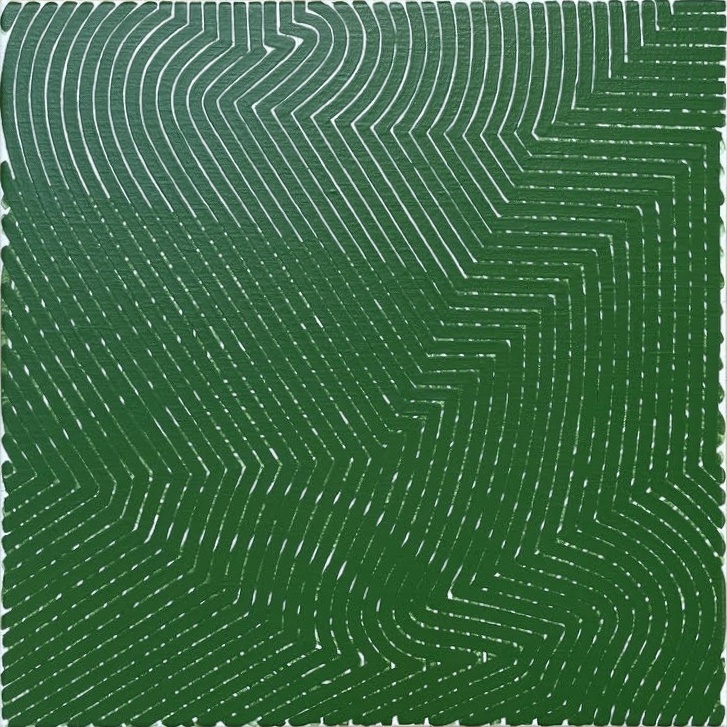

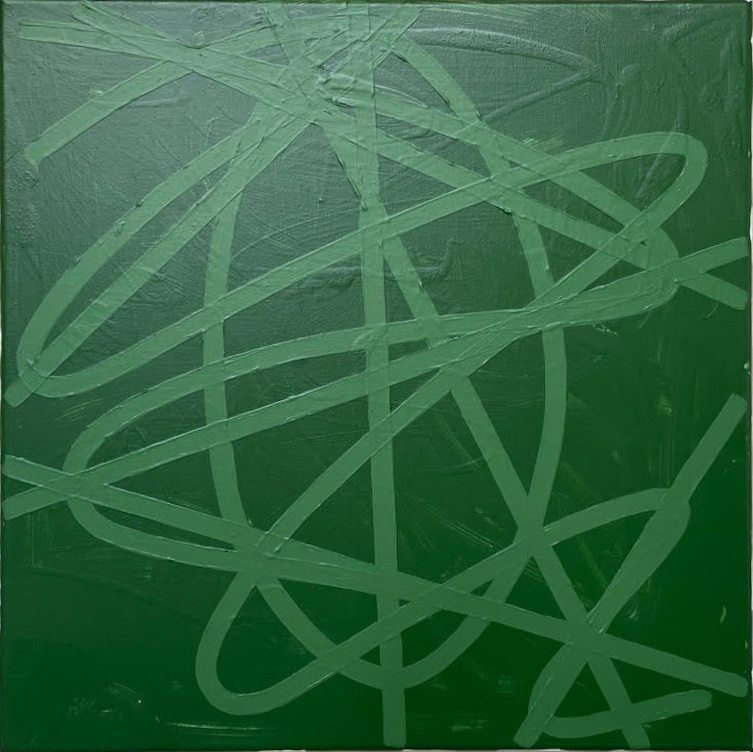

This concerns, then, a monochrome oeuvre–the pencilgrey lines and white plains that also appear in the works do not change this as they provide the ground–with the leading role given to a colour that was considered taboo in abstract modernism. The paintings have fixed measurements (40 x 40cm, 60 x 60cm, 1 x 1m, 2 x 2m), paint gets applied upon canvas by a vast arsenal of means (brush, spray can, roller, spatula, thrown directly from the pot) in the form of graphical motifs (line, whirl, oval, knot, zigzag). The painting’s surface is characterized by painting and drawing, peinture and écriture. In endless variations it is smeared, brushed, scratched and dotted upon. Extremes/absolutes take on forms by way of velvet graffiti, fine needlework, rough sods, and also the energies/spheres that we associate with them: susceptibility, elegance, implacability.

And so the viewer arrives in an arena of a kind in which opposites are pitted against one another (eg. order–frivolity, constraint–freedom, rule–desire). Inner combat, perhaps more palpable beneath the skin than directly visible, makes a return in every single painting. A single work never gives itself away, but is rather reticent and aversive, as if it doesn’t wish to draw or seduce, but rather wants to fasten itself inside the head of the viewer and leave behind a mental imprint. Now let’s give ‘imprint’ an ad-lib typification with the words that Ms. Ives and Dr. Sweet (Penny Dreadful) use for their hero, the undaunted Captain Nemo: swagger, love of freedom and resilience.

modernist hieroglyphs

The work illustrates the complexity of a certain type of art practise that arose in the 1980’s in Western Europe and the U.S., when artists took art history onboard again. At the time conceptual art had reached an impasse; its iconoclasm, its need to break with history–the powers that had given momentum to this trendsetting art of the sixties–no longer worked. Alan McCollum staged such an artistic fatigue by means of a sort of shadow cabinets in which the old medium-specific arts could dazzle the audience, une dernière fois; come the early 80’s, he hung walls full with an endless edition of ‘bedded down’ gypsum paintings (Plaster Surrogates); closely followed by immense displays of vacant vases (Perfect Vehicles).

In short, a contingency plan was devised by a new breed of artists who reclaimed the traditions of the painterly and sculptural art. Rather than shunning this conceptual heritage, more often than not these artists succeeded in interweaving it carefully into their own work. Much like other artists of his generation–e.g. Heimo Zobernig, Stephen Prina and Klaas Kloosterboer–Van Merendonk develops a type of hybrid painting, a variation upon abstract modernism in which the concepts as it were freely roam about. His take on modernism is inspired by a mix of identification and resistance.

Van Merendonk’s paintings trace back to a minimal, almost off-hand drawing from 1983. In the drawing we make out a knot, an oval and a Z; these forms make their return–magnified, fragmented or not–in all subsequent works. The drawing is an archetype, a kind of homunculus that is constantly revivified. This repetitive element, a return of the same aligns his work with geometric abstraction, the esteemed branch of modernist painting that, in search of a spiritual truth, continuously investigated her discoveries by way of a methodically applied course of action.

By introducing a template to which all works must comply, constructing an entire oeuvre from a single drawing, the artist does something else as well, something much larger: he subjects as it were a posteriori the entire tradition of modernist abstraction to a new order, and harasses it with a set of prohibitions, amputations, mutilations, so as to have his painting reflect what can not (or no longer) be done.

This deed brings to the mind the distant memory (or lack thereof) of high modernism, that by the 80’s and most certainly in the globalized 21st century has lost its place. An artist who is still concerned with modernism today, operates in the margins. Van Merendonk’s work is crippled, his monochromes are broken, they have a certain absent-mindedness–compare Günther Förg who traced the earth-bound vestiges of a down-and-out Modernism. The grid, once a framework of concrete horizontal and vertical lines in which a spiritual message resounded, has in Van Merendonk become a ghostly phenomenon, something that lurks beneath the painted surface, a vague echo of ‘the rule’ to which a good modernist artwork once had to comply.

The template that Van Merendonk lays beneath his abstract works brings to mind the operations of conceptual art. This art paved an order of language, measurement, numbers and timescales around the world and broke with illusionism. Conceptual art transferred the focus to the here and now, to experiences of presence, of both the artwork and of ourselves, and to the observation that art lives inside our heads. Van Merendonk requires a similar awareness for that which appears before our eyes. In notions like ‘lacerated monochromatics’ and ‘ghostly grid’ lives a legacy of conceptual art, that wanted to fathom the real world, to perceive what that was like, without fear of disenchantment. But Van Merendonk wants more than to merely put the modernism of say, the 50’s–Newman and Pollock–to the test. He travels back even further in time, and brings a (neo-)primitive Modernism into play. He exchanges Picasso’s tribal motifs for something homemade, which he then applies in his searching for the primordial root of an imaginary modernism.[3] The painter’s moves are ambidextrous: he embraces the tradition of modernist abstraction, but is equally attentive to her ‘holy’ achievements as to her ‘pagan’ potential. So does he arrive at his project, an excavation of modernist hieroglyphs. A site once described by Rosalind Kraus as where everything swarms and proliferates beneath the calm surface of abstract modernist painting.[4]

entropy–quietude

I associate Van Merendonk’s paintings most of all with a number of artists from after the Second World War, the era of Reconstruction. This has most certainly to do with a first impression that I have carried with me for years; i.e., the earthliness of the works, the fact that they remain aloof while they nonetheless clutch themselves on to your gut. Tingueley’s mechanical agility, the scorched earth of Tàpies, and Burri’s fractured surfaces resonate through my experience of Van Merendonk’s work. In 2015 Burri’s Grande Cretto, an impressive land art piece was completed in Gibellina Vechhia in Sicily, a village obliterated by an earthquake in 1968. The artist has covered the remains of an area where once houses stood with a thick cement layer but has left open some of the spaces where formerly the streets ran, so that a new sheath, intersected by various long pavements, covers the old layers.

Of course Tingueley, Tàpies and Burri worked in a period shortly after the Second World War. We encounter the destruction and reconstruction in their art. In Van Merendonk too reality is precarious. In the event of decimation it has the potential to be put back together. The emphasis lies in the natural course of matter, Nature’s Grand Scheme, and the possibility that we may no longer figure in it. He pays heed to things being stuck in the ground, but precisely because roots are unpredictable and beyond our governance. In Van Merendonk paint appears now supple then rigid, now fresh and then full of languor, introvert and/or extravert; and the brush stroke/-cut /-line /-dent /-engraving strengthens this earthly frivolity.

Jos van Merendonk’s wall-installation in Parts Project (The Hague, 6.III–1.V.2016) was a gesamtkunstwerk–the recombining of existing works and motifs dating from a period of almost thirty years. The work was comprised from in situ murals, existing paintings and pieces of old canvas cut from discarded works and ones that had been cast aside. The layered build-up showed, beside the peinture and écriture in their variations, a new excess; spread over the entire wall was a tableau of disorder/entropy. A cartography and calligraphy, both equally striking, crossed paths. The work seemed quite the palimpsest, in which endless layers are stacked on top of each other and the first layer gets repeatedly rewritten by the preceding layer or layers on top of it.

The installation in The Hague was earthly and stout, yet simultaneously hallucinatory and spacey, like an atonal symphony with intriguing dissonance. There was a huge amount on display: throughout the length of the wall were permanent and fleeting shapes, all kinds of green fragments: rigid and fluid lines, soft contours, tight corners, broad strokes, mousey scratches, white planes and stripes, all kinds of flimsy doodles and much swarming about. This visual delirium also had a tacit aspect, which roused the viewer to calmly travel within an inner landscape, a fantasy-in-green, an alchemical tableau.

The entropy and the quietude of this wall-installation, but also the power and inwardness of the paintings tout court form a veritable challenge to a writer to project his thoughts unto them. I would be pleased to write of Van Merendonk’s installation in The Hague as conjoining the sediments of a Burri with the sentiments of a Federle–or rather, holding a balance between the two. But how do I get to such a notion? I’m lambasted by a multitude of associations, precisely because of my initially introverted impression. But can an oeuvre be so jumpy, or is it my brain’s workings? It turns out that Van Merendonk feels connected with a range of painters, who we could call his ‘art-family’, working in many styles, in different places and at different times.

“Considering the nature of my work I could perhaps think it strange that over the past few years, in Berlin and Switzerland, I have been looking at artists like Segantini, Adolf Menzel and Hodler. But it undoubtedly has to do with a wider interest for the 19th century and its offshoots.”

“Also for years I've been familiar with Lucian Freud, Kossof and Auerbach (to name a few ‘English’ artists). I’ve also spent a lot of time viewing the generation of Pollock, De Kooning etc. and the way in which they brought life into abstraction. But in my work one is more likely to see traces of the early Schoonhoven, Dubuffet, Fontana and M. Barré.”

“As for contemporaries I name: Frize, Federle, Lasker, Klaus Merkel, Van den Ende and Wool.”[5]

In this last sentence Helmut Federle strikes me as a remarkable name, his work after all connects traditions of geometric abstraction, their signs and the symbolism thereof, with an incendiary emotional individual spirit. My assertion goes: Van Merendonks work is permeated with romantic irony. By reverting back to romanticism, he renders himself capable of renewing modernism. His design of a (neo-)primitive modernism reminds me of the romantic endeavour; in pursuit of ideals, but aware of the prospect of failure.

romantic irony

Art historians do not agree on what the influence of romanticism is upon modernism; much depends on how one defines the relation between historic romanticism with the enlightenment. Cultural historian Isaiah Berlin considers romanticism as an attack upon the enlightenment, and not as an incongruous movement/inherent counterweight.[6] According to Berlin there comes into being in romanticism the notion that humans are fundamentally different from one another, and that this is a very positive thing. As humans we can certainly think of things in communion, we can share each others beliefs about life and how to arrange the world–and if we do not agree we may discuss matters with one another. But with regard to that which we feel, in our affective positioning within reality, in how the feeling is the compass in our lives, there we differ substantially.[7]

Indeed thinkers, poets and artists towards the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century take their own subjective feeling as a point of departure for their works. It is essential that they remove the affect from their own experience, that they place it before them, as if to dissect it or simply see it more clearly. The example par excellence is of course Friedrich and his paintings of overwhelming experiences snatched from nature, man dissolved and melted into his surroundings. Friedrich's work appeals to our imagination and has a contemporary ambiguity: his works depict total submission but are simultaneously recognizable as constructs of feeling. This ambiguity has in itself become recognisable as a romantic trope/form, as with the fragment (Rodin), the unconditional surrender (Flaubert), and the forging of a new beginning.

In contemporary art romanticism has in my opinion assumed the position of an undercurrent exerting an abiding power of attraction. It has to do with the ambiguity with which its themes are imagined, with irony that acts as a companion to the intensity of (affective) life imagined as art. Van Merendonk: “[What interests me when I start a new work is accomplishing] a new expression, a different face, with a different emptiness.[8] Every day a painting gets made anew–this process can simply take place in one’s head, by way of preparation for the material making–, a painting that needn’t resemble the previous ones and yet is a repetition of the same.

This forging of a new beginning, knowing in advance that the ends are practically unattainable, but in spite of this are worth pursuing, is preeminently a romantic trope/form. We find a prime example in Laurence Sterne, who from 1760 to 1767 worked on his Tristram Shandy, a novel in eight parts in which language stars as the central force. Although three branches of science are discussed–philosophy, fortification, and obstetrics–through the merry discourse of five characters, at the core of the novel stands the recounting of a story. The narrative follows trains of thought, a brushing over of all of the tempting byways that present themselves, causing the reader to get lost in a labyrinth. At whichever passage one picks up this book, the reader will inevitably feel the story to have begun anew.

Van Merendonk’s paintings are fragments of an existing drawing, cut-outs from an infinity of possibilities that is almost overwhelming, and carries silent threats. This has to do with the stealthy orchestration of his extremes/absolutes. In romanticism we see a cultivation of extreme/absolute experiences. The ‘I’ goes beserk on fantasies about himself and the myriad of things he could experience. In art, extremes were put into focus, think of Turner who, in order to physically touch the might of a storm, let himself be tied to the mast of a ship in the middle of the sea. He wished to experience the full thrust of danger, whilst making it home alive and well. Something of that ambiguity is discernible in Jos van Merendonk’s paintings.

Jörg Heiser, the critic/curator, has laid inspiring connections between conceptualism and romanticism in the exhibition Romantic Conceptualism, as well as in various texts.[9] To put it briefly his thesis surmises that conceptual art also deals with a world of feeling, in works where one finds cool detachment and ambiguous irony, emotionally loaded presentations of romantic thought, that are both ‘artifice’ and ‘reality’.

But in order to refresh our understanding of romantic irony, we must go a bit back in time. Irony, of course, plays a large role in the oeuvre of philosopher/theologian Kierkegaard. He investigated the concept in his dissertation, to which he also gave an ironic form. Perhaps he felt the concept presented itself most strongly within a book that would consist solely of prefaces. By doing so, he cultivates the making of a new beginning. From the preface (sic) of this book: “A preface is a mood. Writing a preface is like sharpening a scythe, like tuning a guitar, like talking with a child, like spitting out of the window. (…) Writing a preface is like ringing someone’s doorbell to trick him, like walking by a young lady’s window and gazing at the paving stones; it is like swinging one’s cane in the air to hit the wind, like doffing one’s hat although one is greeting nobody.”[10]

The contemporary artist Stephen Prina makes intriguing work according to this principle of ironic artifice. He has been engaged almost his entire life with building a corpus of works in watercolour with which he redoes the complete works of Manet (a total of 556 according to the catalogue raisonné). What interests Prina in doing so is the time spent by the painter behind his easel, his acts of looking and contemplation in the past, and a modern-day reproduction thereof (Exquisite Corpse: The Complete Paintings of Manet, 1988-today). This work by Prina brings something to the fore that is also a characteristic of Van Merendonk, i.e. being committed to going to the studio, and in committing, practicing, day in day out, every day producing another painting. His work challenges us to translate the commitment of the artist into our own commitment to viewing and, like with conceptual art, to give our attention to the here and now, to that which resides before our own eyes.

Above all his work makes an appeal to ourselves, to our own fantasy, to our very subjectivity, how we deal with art, how we get on with the world, with others, and what we invest of ourselves, how we wish to squander ourselves in the process. A contemporary romantic artist who has repeatedly tempted us to lose ourselves in his filmstories, Jean-Luc Godard, once said this: "Le réel c'est les autres, la fiction c'est soi." While watching Van Merendonk’s paintings, one arrives in the middle of Godard’s fine sentence.

Mark Kremer

translation by Daniel Vorthuys

[1] Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. (Henry Frowde: London etc., 1905), Part 4 Ch. 26, p. 287.

[2] Fernando Pesso, The Book of Disquiet, trans. Richard Zenith (London: The Penguin Press, 2001), p. 30.

[3] Compare Robert Storr on Guillermo Kuitca: "[T]he project in which Kuitca is now engaged seems more a matter of recovering useful fragments of other eras in order to reconstruct painting than of using painting to critique its own heritage from the vantage point of some anticipated future when all its options will have been exhausted. In short, Kuitca appears to have embarked on an archeological tour of the well documented but still partially buried monuments of modernism, curious how their recombinant elements might result in new form." Robert Storr, 'Digging Down', in: Guillermo Kuitca: Plates N˚ 01 – 24 (London: Steidl Hauser & Wirth, 2008), p. 6.

[4] Rosalind Kraus, The Optical Unconscious (Cambridge (MA): The MITT Press, 1993). Here Krauss focuses especially on surrealism and its embrace of irrationality.

[5] E-mail from the artist to the author, 5th of May 2016.

[6] Maarten Doorman, 'De aardbeving van de romantiek: De Menon Lectures van Isaiah Berlin', NRC Handelsblad, 14 januari 2000. See also: <http://www.maartendoorman.nl/index.php?id=904&pid=27>.

[7] Isaiah Berlin, Roots of Romanticism (Pimlico: Chatto & Windus, 1999).

[8] In: Parts Project 01: Bob Law/Jos van Merendonk (Den Haag: Parts Projects, 2016), n.p., brochure of the exhibition To the End of the World or to the Edge of the Paper, text Judith de Bruijn.

[9] Jörg Heiser, Romantic Conceptualism (Kunsthalle Nürnberg, 10.5-15.7 2007); e.g. Jörg Heiser, 'Moscow, Romantic, Conceptualism, and After', <http://www.e-flux.com/journal/moscow-romantic-conceptualism-and-after/>

[10] Nicolaus Notabene, Prefaces, Writing Sampler. Trans. Todd W. Nichol (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), p. 5-6.